Can you pass this pop quiz?

- Which disease (that has no symptoms) precedes the devastating and invariably-fatal presumptive Agent Orange diseases multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis essentially 100% of the time, often by years?

- Which stealth (asymptomatic) disease significantly increases a Veteran’s risk of acquiring a viral infection (including infections caused by respiratory viruses, like the flu) or a bacterial infection?

- Which pre-malignant condition (that significantly reduces longevity) is a Veteran more than twice as likely to contract, if the Veteran was exposed to Agent Orange?

- The occurrence of which disease increases a Veteran’s relative risk (compared to those who do not have the disease) of progressing to an incurable type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (a blood cancer) by over 45 times?

- Which disease requires life-long monitoring to check for progression to malignancies, including presumptive Agent Orange diseases, and occurrence of complications, including heart damage, nerve damage, kidney damage, blood clots, and vision loss?

The answer to all the above questions is monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or MGUS.

MGUS is a disease in which an abnormal protein, known as a monoclonal protein, is produced by white blood cells in bone marrow. MGUS is diagnosed with simple blood tests, some of which are ordinarily run when a Veteran undergoes an Agent Orange Registry health examination. Often MGUS is discovered incidentally during the investigation of other diseases. Because of the disease’s lack of symptoms, a MGUS diagnosis does not support a VA claim for disability compensation, unless a disabling complication occurs. A MGUS diagnosis does, however, support a claim for copayment-exempt (no-cost) medical care for monitoring of a disease that has been clearly shown to be positively associated with Agent Orange exposure by a highly-respected team of researchers from the National Institutes of Health, the Center for Disease Control, and other institutions and by a highly-respected VA clinician.

MGUS is not on the current list of “Agent Orange presumptive diseases” mandated by 38 U.S. Code § 1116. That list is stated by Congress to be “for the purposes of” determinations of disability compensation mandated under 38 U.S. Code § 1110. A petition has been filed with the Secretary of Veterans Affairs requesting that medically-appropriate screening for MGUS (as suggested by Dr. Ola Lundgren, see below) be offered to Vietnam-era Veterans and requesting that MGUS be added to the presumptive diseases list (as suggested by Dr. Nikhil Munshi, see below) to facilitate approval of VA claims for disabilities associated with MGUS sequelae and secondary conditions.

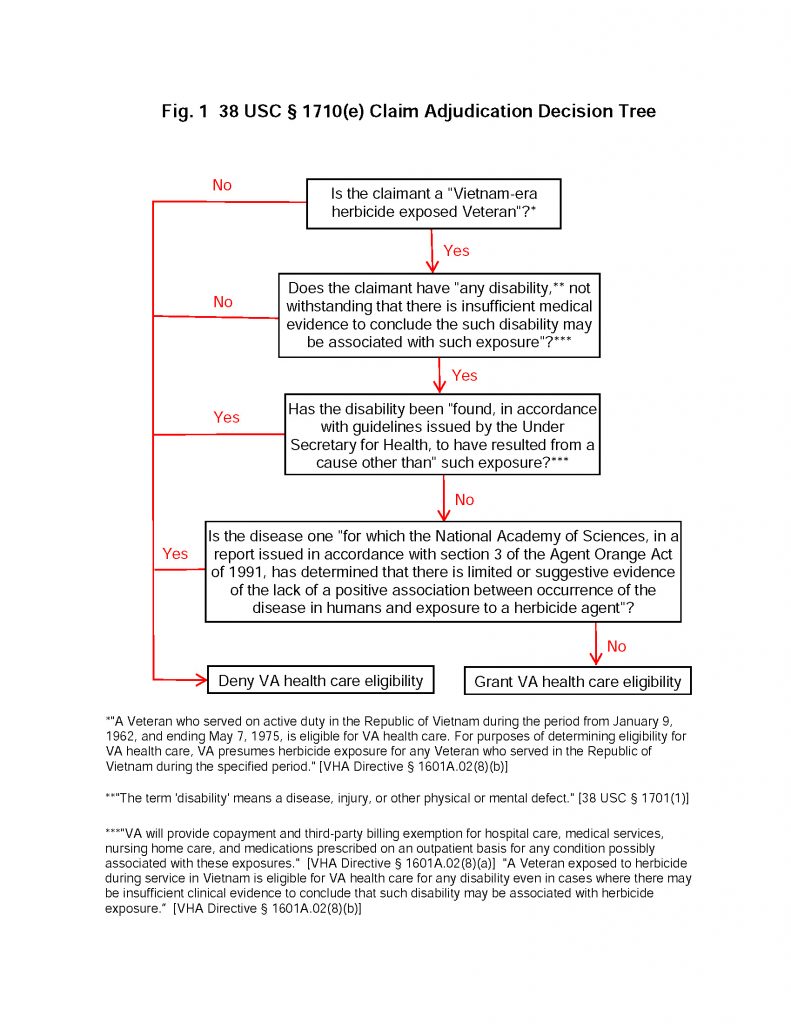

The legal (adjudicative) criteria requiring the VA to provide copayment-exempt medical care to herbicide-exposed veterans mandated by Congress in 38 U.S. Code § 1710(e) and quoted below are different from the legal criteria requiring the VA to provide disability “compensation.” (The term “compensation” means a monthly payment made by the VA to a Veteran or the Veteran’s family because of service-connected disability. 38 U.S. Code § 1701(1) defines the term disability: “The term “disability” means a disease, injury, or other physical or mental defect.”) As explained below, “service connection” is only one way (and not the only way) for a Vietnam-era Veteran to be eligible for no-cost health care for a disease that is possibly associated with Agent Orange exposure.

MGUS Has Been Shown to Be Positively Associated with Agent Orange and Dioxin Exposure of Vietnam-era Veterans

The accepted standard of medical care after MGUS has been diagnosed is life-long follow-up monitoring to detect whether progression to a malignancy or another related condition is occurring. The diseases to which MGUS may progress include the existing presumptive Agent Orange diseases multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma (which includes Waldenström macroglobulinemia and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma), and AL amyloidosis. Recent research has shown that essentially all cases of the devastating Agent Orange diseases multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis are preceded, often by years, by a MGUS diagnosis, and that early treatment of those diseases can improve outcomes. Hence, the need for lifelong MGUS monitoring.

A VA clinician, Dr. Nikhil Munshi of the Boston VA Healthcare System, and an editor of the journal JAMA Oncology, has pointed out that MGUS is related to Agent Orange exposure. In Dr. Nikhil Munshi’s editorial in the American Medical Association’s September 3, 2015 issue of JAMA Oncology, he stated: “The study by Landgren et al. now highlights a strong relationship between Agent Orange exposure and plasma cell disorder, including the development of MGUS, suggesting inclusion of such benign conditions in the list of disorders considered to be Agent Orange related.” The findings of the Landgren et al. research team were published in the same issue of JAMA Oncology in an article entitled “Agent Orange Exposure and Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance: An Operation Ranch Hand Veteran Cohort Study.”

In November 2017, the Director of the Pre-9/11 Era Environmental Health Program (Peter.Rumm@va.gov) asked the committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine preparing the 2018 Veterans and Agent Orange Update 11 to study MGUS as a potential Agent Orange presumptive disease. The leader of the study upon which the above JAMA Oncology article was based, Dr. Ola Landgren (landgrec@mskcc.org), Chief of Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Myeloma Service, provided testimony to the Update 11 committee. In November 2018, the National Academies’ Update 11 (2018) committee issued its report which concluded that “findings strongly support an association between TCDD [a dioxin] exposure and MGUS.” [An explanation of the statistical term “association” is presented on pages 64-68 of Update 11.]

US Law Mandates Veterans’ Eligibility for Copayment-Exempt Medical Care for MGUS

US law mandates copayment-exempt medical care for MGUS because 38 US Code § 1710 exempts Veterans from having to make such payments to the United States in the following situations:

38 US Code § 1710(a)(2)(F) requires the following of the VA: “The Secretary (subject to paragraph (4)) shall furnish hospital care and medical services, and may furnish nursing home care, which the Secretary determines to be needed to any veteran— . . . (F) who was exposed to a toxic substance, radiation, or other conditions, as provided in subsection (e). . . .”

Subsection (e) [aka 38 US Code § 1710(e)(1)(A)] requires the following of the VA: “A Vietnam-era herbicide-exposed veteran is eligible (subject to paragraph (2)) for hospital care, medical services, and nursing home care under subsection (a)(2)(F) for any disability, notwithstanding that there is insufficient medical evidence to conclude that such disability may be associated with such exposure.”

Paragraph 2 [aka 38 US Code § 1710(e)(2)(A)] requires the following of the VA: “In the case of a veteran described in paragraph (1)(A), hospital care, medical services, and nursing home care may not be provided under subsection (a)(2)(F) with respect to—(i) a disability that is found, in accordance with guidelines issued by the Under Secretary for Health, to have resulted from a cause other than an exposure described in paragraph (4)(A)(ii); or (ii) a disease for which the National Academy of Sciences, in a report issued in accordance with section 3 of the Agent Orange Act of 1991, has determined that there is limited or suggestive evidence of the lack of a positive association between occurrence of the disease in humans and exposure to a herbicide agent.” [38 US Code § 1710(e)(2)(A)ii is a low hurdle because the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in its Eleventh Biennial Update found that “there is limited or suggestive evidence of no association between exposure to the herbicide components of interest” in the case of only one of the 58 “health outcomes of herbicide exposure” that it has studied.]

Paragraph 4 [aka 38 US Code § 1710(e)(4)(A)(ii)] requires the following of the VA: “For purposes of this subsection—(A) The term “Vietnam-era herbicide-exposed veteran” means a veteran (i) who served on active duty in the Republic of Vietnam during the period beginning on January 9, 1962, and ending on May 7, 1975, and (ii) who the Secretary finds may have been exposed during such service to dioxin or was exposed during such service to a toxic substance found in a herbicide or defoliant used for military purposes during such period.”

Congress would not have promulgated 38 US Code § 1710(e) if it wanted only the “subchapter II–wartime disability compensation” adjudication criteria of 38 U.S. Code § 1116 to be used in making decisions about the VA’s providing copayment-exempt medical care to Vietnam-era herbicide-exposed Veterans. Furthermore, by promulgating 38 US Code § 1710(e), Congress made it clear that it did not want VA adjudicators to solely rely on the “service-connected disability” adjudication criterion of 38 US Code § 1710(a)(1) in making decisions about the specific issue of the VA’s providing copayment-exempt medical care to Vietnam-era herbicide-exposed Veterans. In short, a Vietnam-era Veteran does not have to be disabled to be eligible for MGUS health care that is cost free to the Veteran.

The Code of Federal Regulations Mandates Veterans’ Eligibility for Copayment-Exempt Medical Care for MGUS

The Code of Federal Regulations mandates copayment-exempt medical care for MGUS because 38 CFR § 17.108 calls for Veterans not to be required to make such payments to the United States in the following situation:

38 CFR § 17.108(e) requires the following of the VA: “(e) Services not subject to copayment requirements for inpatient hospital care, outpatient medical care, or urgent care. The following are not subject to the copayment requirements under this section . . . . (2) Care authorized under 38 US Code § 1710(e) for Vietnam-era herbicide-exposed veterans. . . .”

The VA Under Secretary for Health Is Responsible for Compliance with a VHA Directive That Mandates Eligibility for Copayment-Exempt Medical Care for MGUS

Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1601A.02 (amended October 15, 2020) calls for veterans not to be required to make copayments to the United States in the following situation:

VHA Directive § 1601A.02(8)(a) requires the following of the VA: “Veterans claiming exposure to . . . Agent Orange . . . are provided services in accordance with applicable VA statute and regulation. VA will provide copayment and third-party billing exempt hospital care, medical services, nursing home care, and medications prescribed on an outpatient basis for any condition possibly associated with these exposures. Copayments may be assessed for care not related to the qualifying exposure.”

VHA Directive § 1601A.02(8)(b) requires the following of the VA: “Vietnam-era Herbicide Exposed Veteran. A Veteran who served on active duty in the Republic of Vietnam during the period from January 9, 1962, and ending May 7, 1975, is eligible for VA health care. For purposes of determining eligibility for VA health care, VA presumes herbicide exposure for any Veteran who served in the Republic of Vietnam during the specified period. A Veteran exposed to herbicide during service in Vietnam is eligible for VA health care for any disability even in cases where there may be insufficient clinical evidence to conclude that such disability may be associated with herbicide exposure.”

Summary

In summary, Vietnam-era Veterans are eligible for copayment-exempt (no-cost) health care for monitoring of their MGUS for progression and complications for the following reasons:

Under US law, all Vietnam-era Veterans who served in the Republic of Vietnam are presumed to have been exposed to Agent Orange or a similar herbicide.

The above-referenced Landgren et al. article, the Munshi editorial, a transcript of a JAMA interview of Dr. Landgren and Dr. Munshi about the Landgren et al. research, and the relevant portion of the November 2018, the National Academies’ Eleventh Biennial Update provide competent and credible medical evidence that establishes a nexus between (1) herbicide exposure of Vietnam-era Veterans and (2) the possible development of MGUS. The medical evidence clearly shows that MGUS may be associated with Vietnam-era herbicide exposure which is what is required by 38 US Code § 1710(e). In fact, the medical evidence shows that Agent Orange exposure more than doubled the odds that Vietnam-era herbicide-exposed Veterans would develop MGUS during their lifetimes.

Competent and credible scientific evidence establishes beyond a doubt that MGUS is positively associated with exposure to Agent Orange. To assert otherwise would be to ignore the mandate of Congress in 38 US Code § 1710(e)(1)(A) that Vietnam-era herbicide-exposed Veterans are eligible for copayment-exempt care “notwithstanding that there is insufficient medial evidence to conclude that such disability may be associated with such exposure.” The assertion would also ignore the “may be associated” or “possibly associated” adjudication criteria for copayment-exempt medical care for Vietnam-era herbicide-exposed Veterans quoted above. As noted above, a VA clinician and editor of the highly-respected JAMA Oncology journal has concluded that there is “a strong relationship between Agent Orange exposure and plasma cell disorder, including the development of MGUS.”

Congress made it clear in 38 US Code § 1710(e)(2)(A) that there are only two ways that the VA may deny copayment-exempted health care to herbicide-exposed Veterans for a disease that is possibly associated with such exposure. One way is to produce evidence that supports a finding under the guidelines presented above that another cause resulted in the disease. MGUS cannot definitively be found by the VA to have resulted from a cause other than exposure to Agent Orange during service in Vietnam. Even if the VA harbors such a suspicion or doubt, it is just not medically possible for the VA to definitely identify another cause. Moreover, the VA would have to ignore the adjudication criteria of “may be associated” or “possibly associated” with herbicide exposure. In fact, for the VA to overcome a Veteran’s assertion that the Veteran’s MGUS is possibly associated with Agent Orange exposure would require the VA to find that a preponderance of the evidence shows that Agent Orange exposure was not possibly the cause of the Veteran’s MGUS.

The second way 38 US Code § 1710(e)(2)(A) allows the VA to deny copayment-exempted medical care to herbicide-exposed Veterans for a disease is if the National Academy of Sciences determines that there is limited or suggestive evidence of the lack of a positive association between occurrence of the disease and exposure to a herbicide agent. MGUS is not a disease for which the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) has determined has limited or suggestive evidence of the lack of a positive association between occurrence of the disease and exposure to an herbicide agent. To the contrary, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine have concluded that “findings strongly support an association between TCDD exposure and MGUS.”

It is not possible for the VA to support an assertion that the preponderance of the evidence is against a claim for no-cost health care, and therefore the reasonable doubt doctrine [codified in 38 US Code § 5107(b) and 38 CFR § 3.102 and 38 CFR § 4.3] is not applicable to such claims. In fact, there is absolutely no evidence that MGUS is not “possibly associated” or “may be associated” with Veterans’ herbicide exposure, which are the appropriate adjudication criteria for copayment-exempt medical care for MGUS for Vietnam-era herbicide-exposed Veterans. All of the evidence supports the conclusion that MGUS is positively associated with (and thus also “may be associated” with and is “possibly associated” with) Agent Orange exposure. There is simply no (zero) evidence to the contrary. Because there is not “an approximate balance of positive and negative evidence regarding any issue material to the determination of” such a claim, there is no need for application of the “benefit of the doubt” principle.

A basic principle of statutory interpretation is that a statute should be construed so that effect is given to all its provisions, so that no part will be inoperative or superfluous, void or insignificant. When this principle is applied to 38 US Code § 1710 and MGUS, it is clear that 38 US Code § 1710(e) [which allows a possible association] and not 38 US Code § 1710(a)(1) [which mandates a service connection] or 38 U.S. Code § 1116 [which relies on a presumption] is to be given effect. To do otherwise would render 38 US Code § 1710(e) superfluous, void or insignificant, which was not the intent of Congress.

Another principle of statutory interpretation is that specific terms in a statute prevail over general terms. Thus, however inclusive may be the general language of a statute, it will not be held to apply to an issue specifically dealt with in another part of the enactment. This issue is specifically dealt with in 38 US Code § 1710(e)(1)(A) [in which Congress allows reliance on “insufficient medical evidence” and sets out the adjudication criterion of “may be associated with such exposure”], and 38 CFR § 17.108(e) [which relies on the adjudication criteria of 38 US Code § 1710(e)], and VHA Directive § 1601A.02(8)(a&b) [which set out the adjudication criteria of “possibly associated,” and “may be associated”]. Applying other, more general or inapplicable code sections and ignoring the above VHA Directive would lead VA to make an incorrect decision on such claims.

Conclusion

In summary, Congress created a cohesive and practical approach for the VA to use in making decisions about furnishing no-cost health care to Vietnam-era Veterans who were exposed to herbicides during their service and then developed diseases that were possibly associated with such exposure. The approach is to liberally and sympathetically waive copayments for such health care except where (1) another cause for the disease (other than the exposure) is shown by a preponderance of the evidence or (2) the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine has established a lack of a positive association between the occurrence of the disease and the exposure. The approach was, and still is, more liberal than the approach used to make disability compensation decisions based on service connection rules.

Because research has shown that early detection and subsequent lifetime monitoring of MGUS results in fewer complications and better outcomes for Veterans whose MGUS progresses to other Agent Orange related diseases, the approach codified by Congress benefits all herbicide-exposed Veterans. For all of the above reasons, the VA must use the Congressionally-mandated adjudicative approach illustrated on Figure 1 when deciding such a claim. The author also encourages Veterans and their advocates to remind the VA to use that adjudicative approach with other diseases that have recently been shown to be positively associated with Agent Orange exposure, such as hypertension and dementia, in their claims for cost-free VA healthcare for those diseases.